Verkle trees

2021 Jun 18

See all posts

Verkle trees

Special thanks to Dankrad Feist and Justin Drake for feedback and

review.

Verkle trees are shaping up to be an important part of Ethereum's

upcoming scaling upgrades. They serve the same function as Merkle trees:

you can put a large amount of data into a Verkle tree, and make a short

proof ("witness") of any single piece, or set of pieces, of that data

that can be verified by someone who only has the root of the tree. The

key property that Verkle trees provide, however, is that they are

much more efficient in proof size. If a tree contains a billion

pieces of data, making a proof in a traditional binary Merkle tree would

require about 1 kilobyte, but in a Verkle tree the proof would be

less than 150 bytes - a reduction sufficient to make stateless

clients finally viable in practice.

Verkle trees are still a new idea; they were first introduced by John

Kuszmaul in this

paper from 2018, and they are still not as widely known as many

other important new cryptographic constructions. This post will explain

what Verkle trees are and how the cryptographic magic behind them works.

The price of their short proof size is a higher level of dependence on

more complicated cryptography. That said, the cryptography still much

simpler, in my opinion, than the advanced cryptography found in modern ZK SNARK schemes. In this post I'll do

the best job that I can at explaining it.

Merkle Patricia

vs Verkle Tree node structure

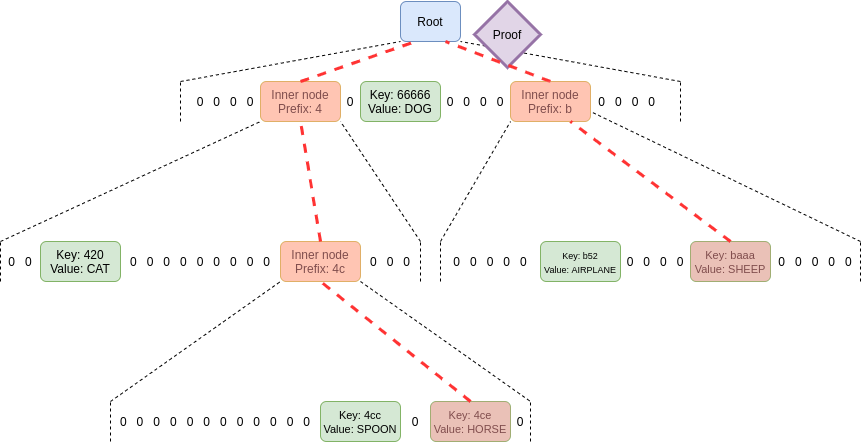

In terms of the structure of the tree (how the nodes in the

tree are arranged and what they contain), a Verkle tree is very similar

to the Merkle

Patricia tree currently used in Ethereum. Every node is either (i)

empty, (ii) a leaf node containing a key and value, or (iii) an

intermediate node that has some fixed number of children (the "width" of

the tree). The value of an intermediate node is computed as a hash of

the values of its children.

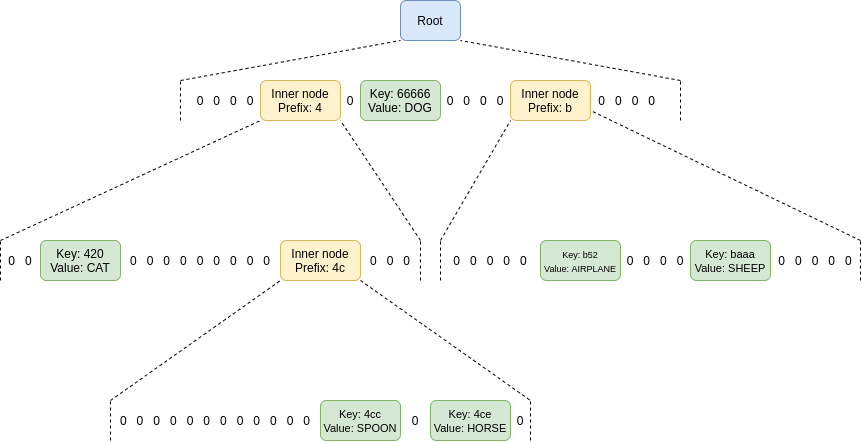

The location of a value in the tree is based on its key: in the

diagram below, to get to the node with key 4cc, you start

at the root, then go down to the child at position 4, then

go down to the child at position c (remember:

c = 12 in hexadecimal), and then go down again to the child

at position c. To get to the node with key

baaa, you go to the position-b child of the

root, and then the position-a child of that node.

The node at path (b,a) directly contains the node with key

baaa, because there are no other keys in the tree starting

with ba.

The structure of nodes in a hexary (16 children per parent)

Verkle tree, here filled with six (key, value)

pairs.

The only real difference in the structure of Verkle trees

and Merkle Patricia trees is that Verkle trees are wider in practice.

Much wider. Patricia trees are at their most efficient when

width = 2 (so Ethereum's hexary Patricia tree is actually

quite suboptimal). Verkle trees, on the other hand, get shorter and

shorter proofs the higher the width; the only limit is that if width

gets too high, proofs start to take too long to create. The Verkle tree

proposed for Ethereum has a width of 256, and some even favor

raising it to 1024 (!!).

Commitments and proofs

In a Merkle tree (including Merkle Patricia trees), the proof of a

value consists of the entire set of sister nodes: the proof

must contain all nodes in the tree that share a parent with any

of the nodes in the path going down to the node you are trying to prove.

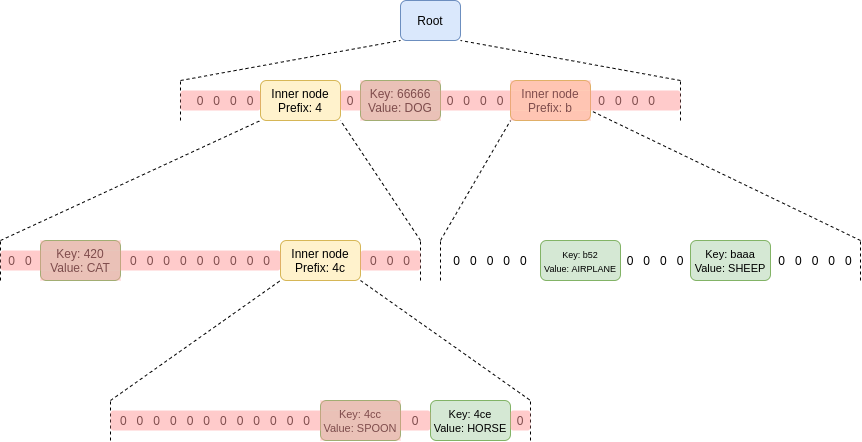

That may be a little complicated to understand, so here's a picture of a

proof for the value in the 4ce position. Sister nodes that

must be included in the proof are highlighted in red.

That's a lot of nodes! You need to provide the sister nodes at each

level, because you need the entire set of children of a node to compute

the value of that node, and you need to keep doing this until you get to

the root. You might think that this is not that bad because most of the

nodes are zeroes, but that's only because this tree has very few nodes.

If this tree had 256 randomly-allocated nodes, the top layer would

almost certainly have all 16 nodes full, and the second layer would on

average be ~63.3% full.

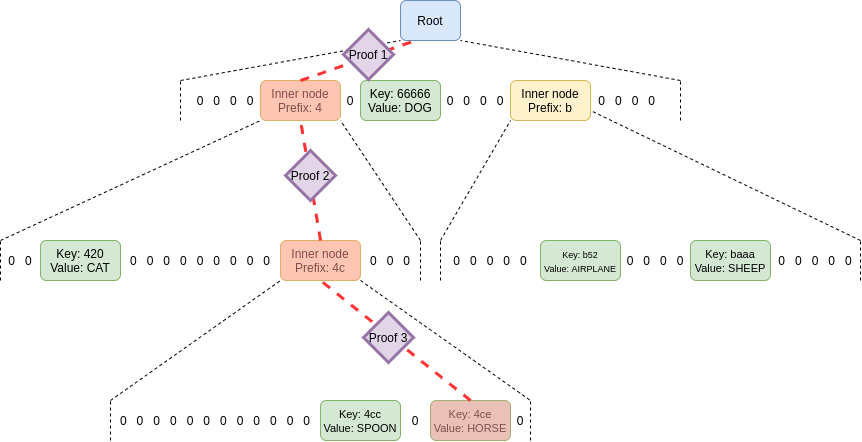

In a Verkle tree, on the other hand, you do not need to

provide sister nodes; instead, you just provide the path, with a little

bit extra as a proof. This is why Verkle trees benefit from

greater width and Merkle Patricia trees do not: a tree with greater

width leads to shorter paths in both cases, but in a Merkle Patricia

tree this effect is overwhelmed by the higher cost of needing to provide

all the width - 1 sister nodes per level in a proof. In a

Verkle tree, that cost does not exist.

So what is this little extra that we need as a proof? To understand

that, we first need to circle back to one key detail: the hash function

used to compute an inner node from its children is not a regular hash.

Instead, it's a vector commitment.

A vector commitment scheme is a special type of hash function,

hashing a list \(h(z_1, z_2 ... z_n)

\rightarrow C\). But vector commitments have the special property

that for a commitment \(C\) and a value

\(z_i\), it's possible to make a short

proof that \(C\) is the commitment to

some list where the value at the i'th position is \(z_i\). In a Verkle proof, this short proof

replaces the function of the sister nodes in a Merkle Patricia proof,

giving the verifier confidence that a child node really is the child at

the given position of its parent node.

No sister nodes required in a proof of a value in the tree;

just the path itself plus a few short proofs to link each commitment in

the path to the next.

In practice, we use a primitive even more powerful than a vector

commitment, called a polynomial commitment. Polynomial

commitments let you hash a polynomial, and make a proof for the

evaluation of the hashed polynomial at any point. You can use

polynomial commitments as vector commitments: if we agree on a set of

standardized coordinates \((c_1, c_2 ...

c_n)\), given a list \((y_1, y_2 ...

y_n)\) you can commit to the polynomial \(P\) where \(P(c_i) = y_i\) for all \(i \in [1..n]\) (you can find this

polynomial with Lagrange

interpolation). I talk about polynomial commitments at length in my

article on ZK-SNARKs. The two polynomial commitment schemes that are

the easiest to use are KZG

commitments and bulletproof-style

commitments (in both cases, a commitment is a single 32-48 byte

elliptic curve point). Polynomial commitments give us more flexibility

that lets us improve efficiency, and it just so happens that the

simplest and most efficient vector commitments available are

the polynomial commitments.

This scheme is already very powerful as it is: if you use a

KZG commitment and proof, the proof size is 96 bytes per intermediate

node, nearly 3x more space-efficient than a simple Merkle proof

if we set width = 256. However, it turns out that we can increase

space-efficiency even further.

Merging the proofs

Instead of requiring one proof for each commitment along the path,

by using the extra properties of polynomial commitments we can

make a single fixed-size proof that proves all parent-child

links between commitments along the paths for an unlimited number of

keys. We do this using a scheme

that implements multiproofs through random evaluation.

But to use this scheme, we first need to convert the problem into a

more structured one. We have a proof of one or more values in a Verkle

tree. The main part of this proof consists of the intermediary nodes

along the path to each node. For each node that we provide, we also have

to prove that it actually is the child of the node above it (and in the

correct position). In our single-value-proof example above, we needed

proofs to prove:

- That the

key: 4ce node actually is the

position-e child of the prefix: 4c

intermediate node.

- That the

prefix: 4c intermediate node actually is the

position-c child of the prefix: 4 intermediate

node.

- That the

prefix: 4 intermediate node actually is the

position-4 child of the root

If we had a proof proving multiple values (eg. both 4ce

and 420), we would have even more nodes and even more

linkages. But in any case, what we are proving is a sequence of

statements of the form "node A actually is the position-i child of node

B". If we are using polynomial commitments, this turns into

equations: \(A(x_i) = y\), where \(y\) is the hash of the commitment to \(B\).

The details of this proof are technical and better explained

by Dankrad Feist than myself. By far the bulkiest and time-consuming

step in the proof generation involves computing a polynomial \(g\) of the form:

\(g(X) = r^0\frac{A_0(X) - y_0}{X - x_0} +

r^1\frac{A_1(X) - y_1}{X - x_1} + ... + r^n\frac{A_n(X) - y_n}{X -

x_n}\)

It is only possible to compute each term \(r^i\frac{A_i(X) - y_i}{X - x_i}\) if that

expression is a polynomial (and not a fraction). And that requires \(A_i(X)\) to equal \(y_i\) at the point \(x_i\).

We can see this with an example. Suppose:

- \(A_i(X) = X^2 + X + 3\)

- We are proving for \((x_i = 2, y_i =

9)\). \(A_i(2)\) does equal

\(9\) so this will work.

\(A_i(X) - 9 = X^2 + X - 6\), and

\(\frac{X^2 + X - 6}{X - 2}\) gives a

clean \(X - 3\). But if we tried to fit

in \((x_i = 2, y_i = 10)\), this would

not work; \(X^2 + X - 7\)

cannot be cleanly divided by \(X -

2\) without a fractional remainder.

The rest of the proof involves providing a polynomial commitment to

\(g(X)\) and then proving that the

commitment is actually correct. Once again, see Dankrad's

more technical description for the rest of the proof.

One single proof proves an unlimited number of parent-child

relationships.

And there we have it, that's what a maximally efficient Verkle proof

looks like.

Key properties

of proof sizes using this scheme

- Dankrad's multi-random-evaluation proof allows the prover to

prove an arbitrary number of evaluations \(A_i(x_i) = y_i\), given

commitments to each \(A_i\) and the

values that are being proven. This proof is constant

size (one polynomial commitment, one number, and two proofs;

128-1000 bytes depending on what scheme is being used).

- The \(y_i\) values do not

need to be provided explicitly, as they can be directly

computed from the other values in the Verkle proof: each \(y_i\) is itself the hash of the next value

in the path (either a commitment or a leaf).

- The \(x_i\) values also do

not need to be provided explicitly, since the paths (and hence

the \(x_i\) values) can be computed

from the keys and the coordinates derived from the paths.

- Hence, all we need is the leaves (keys and values) that we

are proving, as well as the commitments along the path from each leaf to

the root.

- Assuming a width-256 tree, and \(2^{32}\) nodes, a proof would require the

keys and values that are being proven, plus (on average) three

commitments for each value along the path from that value to

the root.

- If we are proving many values, there are further

savings: no matter how many values you are proving, you will

not need to provide more than the 256 values at the top level.

Proof

sizes (bytes). Rows: tree size, cols: key/value pairs proven

| 256 |

176 |

176 |

176 |

176 |

176 |

| 65,536 |

224 |

608 |

4,112 |

12,176 |

12,464 |

| 16,777,216 |

272 |

1,040 |

8,864 |

59,792 |

457,616 |

| 4,294,967,296 |

320 |

1,472 |

13,616 |

107,744 |

937,472 |

Assuming width 256, and 48-byte KZG commitments/proofs. Note also

that this assumes a maximally even tree; for a realistic randomized

tree, add a depth of ~0.6 (so ~30 bytes per element). If

bulletproof-style commitments are used instead of KZG, it's safe to go

down to 32 bytes, so these sizes can be reduced by 1/3.

Prover and verifier

computation load

The bulk of the cost of generating a proof is

computing each \(r^i\frac{A_i(X) - y_i}{X -

x_i}\) expression. This requires roughly four field operations

(ie. 256 bit modular arithmetic operations) times the width of the tree.

This is the main constraint limiting Verkle tree widths. Fortunately,

four field operations is a small cost: a single elliptic curve

multiplication typically takes hundreds of field operations. Hence,

Verkle tree widths can go quite high; width 256-1024 seems like an

optimal range.

To edit the tree, we need to "walk up the

tree" from the leaf to the root, changing the intermediate commitment at

each step to reflect the change that happened lower down. Fortunately,

we don't have to re-compute each commitment from scratch. Instead, we

take advantage of the homomorphic property: given a polynomial

commitment \(C = com(F)\), we can

compute \(C' = com(F + G)\) by

taking \(C' = C + com(G)\). In our

case, \(G = L_i * (v_{new} -

v_{old})\), where \(L_i\) is a

pre-computed commitment for the polynomial that equals 1 at the position

we're trying to change and 0 everywhere else.

Hence, a single edit requires ~4 elliptic curve multiplications (one

per commitment between the leaf and the root, this time including the

root), though these can be sped up considerably by pre-computing and

storing many multiples of each \(L_i\).

Proof verification is quite efficient. For a proof

of N values, the verifier needs to do the following steps, all of which

can be done within a hundred milliseconds for even thousands of

values:

- One size-\(N\) elliptic

curve fast linear combination

- About \(4N\) field operations (ie.

256 bit modular arithmetic operations)

- A small constant amount of work that does not depend on the size of

the proof

Note also that, like Merkle Patricia proofs, a Verkle proof gives the

verifier enough information to modify the values in the tree

that are being proven and compute the new root hash after the changes

are applied. This is critical for verifying that eg. state changes in a

block were processed correctly.

Conclusions

Verkle trees are a powerful upgrade to Merkle proofs that allow for

much smaller proof sizes. Instead of needing to provide all "sister

nodes" at each level, the prover need only provide a single proof that

proves all parent-child relationships between all commitments

along the paths from each leaf node to the root. This allows proof sizes

to decrease by a factor of ~6-8 compared to ideal Merkle trees, and by a

factor of over 20-30 compared to the hexary Patricia trees that Ethereum

uses today (!!).

They do require more complex cryptography to implement, but they

present the opportunity for large gains to scalability. In the medium

term, SNARKs can improve things further: we can either SNARK the

already-efficient Verkle proof verifier to reduce witness size to

near-zero, or switch back to SNARKed Merkle proofs if/when SNARKs get

much better (eg. through

GKR, or very-SNARK-friendly hash functions, or ASICs). Further down

the line, the rise of quantum computing will force a change to STARKed

Merkle proofs with hashes as it makes the linear homomorphisms that

Verkle trees depend on insecure. But for now, they give us the same

scaling gains that we would get with such more advanced technologies,

and we already have all the tools that we need to implement them

efficiently.

Verkle trees

2021 Jun 18 See all postsSpecial thanks to Dankrad Feist and Justin Drake for feedback and review.

Verkle trees are shaping up to be an important part of Ethereum's upcoming scaling upgrades. They serve the same function as Merkle trees: you can put a large amount of data into a Verkle tree, and make a short proof ("witness") of any single piece, or set of pieces, of that data that can be verified by someone who only has the root of the tree. The key property that Verkle trees provide, however, is that they are much more efficient in proof size. If a tree contains a billion pieces of data, making a proof in a traditional binary Merkle tree would require about 1 kilobyte, but in a Verkle tree the proof would be less than 150 bytes - a reduction sufficient to make stateless clients finally viable in practice.

Verkle trees are still a new idea; they were first introduced by John Kuszmaul in this paper from 2018, and they are still not as widely known as many other important new cryptographic constructions. This post will explain what Verkle trees are and how the cryptographic magic behind them works. The price of their short proof size is a higher level of dependence on more complicated cryptography. That said, the cryptography still much simpler, in my opinion, than the advanced cryptography found in modern ZK SNARK schemes. In this post I'll do the best job that I can at explaining it.

Merkle Patricia vs Verkle Tree node structure

In terms of the structure of the tree (how the nodes in the tree are arranged and what they contain), a Verkle tree is very similar to the Merkle Patricia tree currently used in Ethereum. Every node is either (i) empty, (ii) a leaf node containing a key and value, or (iii) an intermediate node that has some fixed number of children (the "width" of the tree). The value of an intermediate node is computed as a hash of the values of its children.

The location of a value in the tree is based on its key: in the diagram below, to get to the node with key

4cc, you start at the root, then go down to the child at position4, then go down to the child at positionc(remember:c = 12in hexadecimal), and then go down again to the child at positionc. To get to the node with keybaaa, you go to the position-bchild of the root, and then the position-achild of that node. The node at path(b,a)directly contains the node with keybaaa, because there are no other keys in the tree starting withba.The structure of nodes in a hexary (16 children per parent) Verkle tree, here filled with six (key, value) pairs.

The only real difference in the structure of Verkle trees and Merkle Patricia trees is that Verkle trees are wider in practice. Much wider. Patricia trees are at their most efficient when

width = 2(so Ethereum's hexary Patricia tree is actually quite suboptimal). Verkle trees, on the other hand, get shorter and shorter proofs the higher the width; the only limit is that if width gets too high, proofs start to take too long to create. The Verkle tree proposed for Ethereum has a width of 256, and some even favor raising it to 1024 (!!).Commitments and proofs

In a Merkle tree (including Merkle Patricia trees), the proof of a value consists of the entire set of sister nodes: the proof must contain all nodes in the tree that share a parent with any of the nodes in the path going down to the node you are trying to prove. That may be a little complicated to understand, so here's a picture of a proof for the value in the

4ceposition. Sister nodes that must be included in the proof are highlighted in red.That's a lot of nodes! You need to provide the sister nodes at each level, because you need the entire set of children of a node to compute the value of that node, and you need to keep doing this until you get to the root. You might think that this is not that bad because most of the nodes are zeroes, but that's only because this tree has very few nodes. If this tree had 256 randomly-allocated nodes, the top layer would almost certainly have all 16 nodes full, and the second layer would on average be ~63.3% full.

In a Verkle tree, on the other hand, you do not need to provide sister nodes; instead, you just provide the path, with a little bit extra as a proof. This is why Verkle trees benefit from greater width and Merkle Patricia trees do not: a tree with greater width leads to shorter paths in both cases, but in a Merkle Patricia tree this effect is overwhelmed by the higher cost of needing to provide all the

width - 1sister nodes per level in a proof. In a Verkle tree, that cost does not exist.So what is this little extra that we need as a proof? To understand that, we first need to circle back to one key detail: the hash function used to compute an inner node from its children is not a regular hash. Instead, it's a vector commitment.

A vector commitment scheme is a special type of hash function, hashing a list \(h(z_1, z_2 ... z_n) \rightarrow C\). But vector commitments have the special property that for a commitment \(C\) and a value \(z_i\), it's possible to make a short proof that \(C\) is the commitment to some list where the value at the i'th position is \(z_i\). In a Verkle proof, this short proof replaces the function of the sister nodes in a Merkle Patricia proof, giving the verifier confidence that a child node really is the child at the given position of its parent node.

No sister nodes required in a proof of a value in the tree; just the path itself plus a few short proofs to link each commitment in the path to the next.

In practice, we use a primitive even more powerful than a vector commitment, called a polynomial commitment. Polynomial commitments let you hash a polynomial, and make a proof for the evaluation of the hashed polynomial at any point. You can use polynomial commitments as vector commitments: if we agree on a set of standardized coordinates \((c_1, c_2 ... c_n)\), given a list \((y_1, y_2 ... y_n)\) you can commit to the polynomial \(P\) where \(P(c_i) = y_i\) for all \(i \in [1..n]\) (you can find this polynomial with Lagrange interpolation). I talk about polynomial commitments at length in my article on ZK-SNARKs. The two polynomial commitment schemes that are the easiest to use are KZG commitments and bulletproof-style commitments (in both cases, a commitment is a single 32-48 byte elliptic curve point). Polynomial commitments give us more flexibility that lets us improve efficiency, and it just so happens that the simplest and most efficient vector commitments available are the polynomial commitments.

This scheme is already very powerful as it is: if you use a KZG commitment and proof, the proof size is 96 bytes per intermediate node, nearly 3x more space-efficient than a simple Merkle proof if we set width = 256. However, it turns out that we can increase space-efficiency even further.

Merging the proofs

Instead of requiring one proof for each commitment along the path, by using the extra properties of polynomial commitments we can make a single fixed-size proof that proves all parent-child links between commitments along the paths for an unlimited number of keys. We do this using a scheme that implements multiproofs through random evaluation.

But to use this scheme, we first need to convert the problem into a more structured one. We have a proof of one or more values in a Verkle tree. The main part of this proof consists of the intermediary nodes along the path to each node. For each node that we provide, we also have to prove that it actually is the child of the node above it (and in the correct position). In our single-value-proof example above, we needed proofs to prove:

key: 4cenode actually is the position-echild of theprefix: 4cintermediate node.prefix: 4cintermediate node actually is the position-cchild of theprefix: 4intermediate node.prefix: 4intermediate node actually is the position-4child of the rootIf we had a proof proving multiple values (eg. both

4ceand420), we would have even more nodes and even more linkages. But in any case, what we are proving is a sequence of statements of the form "node A actually is the position-i child of node B". If we are using polynomial commitments, this turns into equations: \(A(x_i) = y\), where \(y\) is the hash of the commitment to \(B\).The details of this proof are technical and better explained by Dankrad Feist than myself. By far the bulkiest and time-consuming step in the proof generation involves computing a polynomial \(g\) of the form:

\(g(X) = r^0\frac{A_0(X) - y_0}{X - x_0} + r^1\frac{A_1(X) - y_1}{X - x_1} + ... + r^n\frac{A_n(X) - y_n}{X - x_n}\)

It is only possible to compute each term \(r^i\frac{A_i(X) - y_i}{X - x_i}\) if that expression is a polynomial (and not a fraction). And that requires \(A_i(X)\) to equal \(y_i\) at the point \(x_i\).

We can see this with an example. Suppose:

\(A_i(X) - 9 = X^2 + X - 6\), and \(\frac{X^2 + X - 6}{X - 2}\) gives a clean \(X - 3\). But if we tried to fit in \((x_i = 2, y_i = 10)\), this would not work; \(X^2 + X - 7\) cannot be cleanly divided by \(X - 2\) without a fractional remainder.

The rest of the proof involves providing a polynomial commitment to \(g(X)\) and then proving that the commitment is actually correct. Once again, see Dankrad's more technical description for the rest of the proof.

One single proof proves an unlimited number of parent-child relationships.

And there we have it, that's what a maximally efficient Verkle proof looks like.

Key properties of proof sizes using this scheme

Proof sizes (bytes). Rows: tree size, cols: key/value pairs proven

Assuming width 256, and 48-byte KZG commitments/proofs. Note also that this assumes a maximally even tree; for a realistic randomized tree, add a depth of ~0.6 (so ~30 bytes per element). If bulletproof-style commitments are used instead of KZG, it's safe to go down to 32 bytes, so these sizes can be reduced by 1/3.

Prover and verifier computation load

The bulk of the cost of generating a proof is computing each \(r^i\frac{A_i(X) - y_i}{X - x_i}\) expression. This requires roughly four field operations (ie. 256 bit modular arithmetic operations) times the width of the tree. This is the main constraint limiting Verkle tree widths. Fortunately, four field operations is a small cost: a single elliptic curve multiplication typically takes hundreds of field operations. Hence, Verkle tree widths can go quite high; width 256-1024 seems like an optimal range.

To edit the tree, we need to "walk up the tree" from the leaf to the root, changing the intermediate commitment at each step to reflect the change that happened lower down. Fortunately, we don't have to re-compute each commitment from scratch. Instead, we take advantage of the homomorphic property: given a polynomial commitment \(C = com(F)\), we can compute \(C' = com(F + G)\) by taking \(C' = C + com(G)\). In our case, \(G = L_i * (v_{new} - v_{old})\), where \(L_i\) is a pre-computed commitment for the polynomial that equals 1 at the position we're trying to change and 0 everywhere else.

Hence, a single edit requires ~4 elliptic curve multiplications (one per commitment between the leaf and the root, this time including the root), though these can be sped up considerably by pre-computing and storing many multiples of each \(L_i\).

Proof verification is quite efficient. For a proof of N values, the verifier needs to do the following steps, all of which can be done within a hundred milliseconds for even thousands of values:

Note also that, like Merkle Patricia proofs, a Verkle proof gives the verifier enough information to modify the values in the tree that are being proven and compute the new root hash after the changes are applied. This is critical for verifying that eg. state changes in a block were processed correctly.

Conclusions

Verkle trees are a powerful upgrade to Merkle proofs that allow for much smaller proof sizes. Instead of needing to provide all "sister nodes" at each level, the prover need only provide a single proof that proves all parent-child relationships between all commitments along the paths from each leaf node to the root. This allows proof sizes to decrease by a factor of ~6-8 compared to ideal Merkle trees, and by a factor of over 20-30 compared to the hexary Patricia trees that Ethereum uses today (!!).

They do require more complex cryptography to implement, but they present the opportunity for large gains to scalability. In the medium term, SNARKs can improve things further: we can either SNARK the already-efficient Verkle proof verifier to reduce witness size to near-zero, or switch back to SNARKed Merkle proofs if/when SNARKs get much better (eg. through GKR, or very-SNARK-friendly hash functions, or ASICs). Further down the line, the rise of quantum computing will force a change to STARKed Merkle proofs with hashes as it makes the linear homomorphisms that Verkle trees depend on insecure. But for now, they give us the same scaling gains that we would get with such more advanced technologies, and we already have all the tools that we need to implement them efficiently.